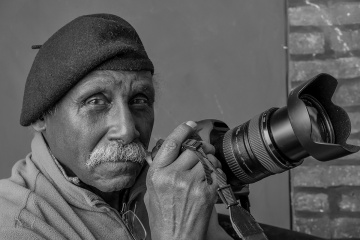

Veteran photographer Adger Cowans is still learning at 81

An interview with veteran photographer Adger Cowans

• June 2018 issue

Sitting in his packed-to-the-gills apartment/studio in Bridgeport, Connecticut, photographer Adger Cowans smiles as he launches into a story from what he calls his distant past. Legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland had summoned him to her office for an assignment. Cowans, who is 81 but looks a decade younger, punctuates his story with spirited hand gestures, darting eyebrows, and the occasional high-octane chuckle.

“This was in the 1960s, and she had seen an exhibit of my photographs at a gallery on Fifth Avenue in New York City. She thought I’d be perfect for a fashion shoot, so she called me in,” says Cowans with a twinkle in his eyes. “But when I walked into her office, she did a double take ... like this.” Cowans snaps his head up and down sharply, and laughs. “I had a big, out-to-here Afro back then and always wore dark shades and a Levi’s denim suit. I was cool.”

He loves telling this story, nearly doubling over in giggles before he comes to the punch line: “I immediately knew what she was thinking before she said a word. She told me, ‘Oh my, Mr. Cowans, I am so happy to meet you. But I didn’t know you were a Negro. I am so sorry.’”

Cowans said nothing. Vreeland was embarrassed. She explained that the Vogue assignment involved photographing white fashion models in the South. “I just don’t think it would work out,” he recalls her saying. “It would be impossible.”

“You know, that’s just the way things were back then in the 1960s,” says Cowans. “There were hardly any black photographers around.” Before breaking into a hearty laugh, he adds, “And to tell you the truth, at the time I wasn’t too thrilled about the idea of going down South to photograph white women, either!”

The story is quintessential Cowans. He doesn’t let others’ perceptions of him get under his skin and uses his keen sense of humor to lighten the mood. “I was black when I was born, and I’ve had to deal with it all my life,” says Cowans with a smile. “My mother said if someone calls you a name, they don’t know who you are. It’s on them, not you. It was something I’ve never forgotten.”

The Vreeland story had a happy ending. “I could have stormed out of her office, but I didn’t. I knew what was going on, what the deal was.” A week later she called and offered him a semi-regular job photographing fashion models at the magazine’s studios. “I took it. It was good money,” recalls Cowans, “but after a few months I got tired of it and moved on.”

Lifetime of learning

As he continues working into his ninth decade, Cowans is widely celebrated as one of the country’s most accomplished black photographers. The Columbus, Ohio, native earned a BFA in photography from Ohio University in 1958, where he studied under Clarence H. White Jr., and later with Minor White. He’s won numerous awards and fellowships and has a varied portfolio of commercial and personal work.

His lifetime of work was recently published in the book “Personal Vision.” His photographs have been shown by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Harvard Fine Art Museum, the International Museum of Photography, and numerous other art institutions. The New York Times described one of his many one-man shows as, “Boldly inventive and experimental ... and the artist is a craftsman to his fingertips.” The legendary photographer Gordon Parks, for whom Cowans once worked, called him “one of the most significant artists of our time,” and noted, “Adger’s individualism sets him apart, simply because he follows his own convictions.”

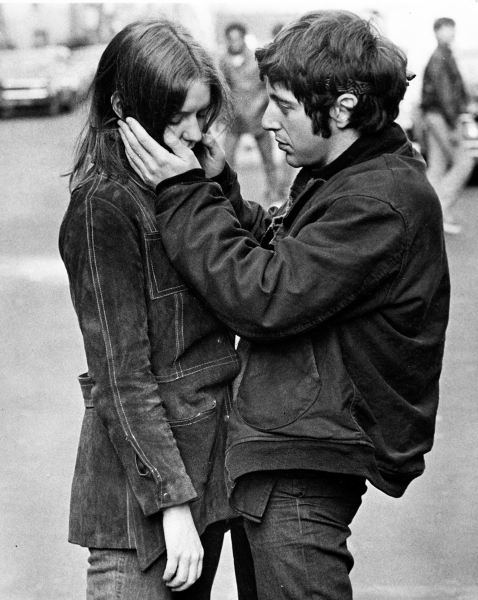

Flipping through Cowans’ six-decades-deep portfolio is like taking a trip through the history of modern American photography. His portrait subjects include Malcolm X, Dizzy Gillespie, Faye Dunaway, Katherine Hepburn, and Ice-T. His subject matter is also varied—the civil rights movement, Hollywood celebrities (he was the stills photographer for more than 30 movies), evocative Harlem street scenes, and personal artistic studies of water and light. “I’m 81 and sometimes I think I’ve seen it all,” Cowans says. “But I’m still learning.”

Spotting a picture he took in college gets him reminiscing. “You have to remember that in my college days there were hardly any photography magazines or books back then; Beaumont Newhall’s ‘History of Photography’ was about it. But we were lucky enough, thanks to Clarence H. White Jr.’s father, to be able to study actual prints made by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, W. Eugene Smith, and others. This was before these cats became world-famous.”

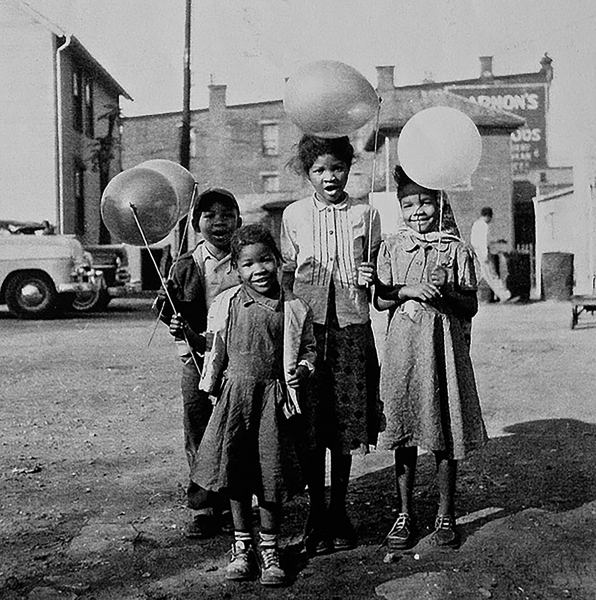

He pauses at one of his most famous images, a shot of four black children in Columbus, Ohio, each with a balloon and a big smile. “I have a confession about this picture,” he says. “I took this picture when I was a teenager, but it wasn’t until I was much older that I understood how much power it had to move people and how I had to trust myself to find that power.”

He spotted the children on the street in his hometown and saw them looking “longingly” at a balloon salesman. “I knew they didn’t have any money so I bought them balloons and thought I might be able to get their reaction. I was hoping to capture something. And I did.

“Later I realized that every time I took a picture I had been trying to capture a feeling, an emotion—just like I did back then. You take a picture with your heart and not with your eyes. The eyes see what the heart feels. You have to be there first—recognizing pain or joy or whatever—in order to show it to the viewer. That’s the artist’s job and it’s why I love my work.”

Capturing that emotion means being ready, says Cowans, reaching for his new Leica V-Lux to show how he spent years “practicing” or “rehearsing” with his first cameras in the 1950s and later. “I spent countless hours picking up my camera—without film—adjusting the focus, setting the aperture, adjusting the speed, clicking the shutter. It was like playing the scales when I learned to play the piano. In the same way I have always practiced seeing. I look at everything—light movement, form—everything. I practice with my eyes until it becomes second nature, like riding a bike,” he says as he simulates adjusting a camera and clicking off a shot.

From his perch on the couch he raises his new digital camera to his eyes and frames me in the viewfinder. “I have to be ready for those moments—those moments that fly by—when someone or something would reveal themselves to me,” he says as he presses the shutter release. “It’s all about that moment.”

It’s the work that matters

While Cowans has received a slew of awards and recognition for his work, he readily admits, “I’m not a big, big name.” Indeed, while praising his lifetime of work The New York Times recently described him as “an important but under-known photographer.” How does he feel about that?

“I think part of it is that I don’t really care about being famous. Never have,” Cowans says.

“Really?” I ask him.

“Really! Never did! I am 81 and still working and happy to be doing my own thing, even if it’s in the shadows. It’s the work that matters.” He lets out a loud belly laugh and adds, “The work! Now, that’s what’s cool!”

RELATED: A gallery of Adger Cowans' images

RELATED: Adger Cowans' personal photography is a bit of a mystery

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont.

View Gallery

View Gallery