In living color

Dean Bradshow shows that the most powerful commercial photographs tell a story.

• November 2015 issue

Dean Bradshaw's real is more vivid than reality

Commercial photographer Dean Bradshaw has just returned from Mongolia. He spent almost a month photographing traditional wrestling, horse racing, and archery competitions at the Naadam Festival and then traveled to the Russian border to capture portraits of Mongolian eagle hunters. Bradshaw’s client for this work: himself.

He’s not selling these images, but he’ll include them in a gallery on his website, where they could excite an art director and lead to an assignment. “Personal work is often what gets people’s attention,” Bradshaw says. “Everyone sees ads everyday and doesn’t get excited by them. Personal projects kind of say who you are.” Truth be told, though, the primary purpose of the Mongolian photo shoot was to give Bradshaw an excuse to travel there and experience the culture. “Photography is the way I connect with the world, and it allows me to go to these places you normally don’t go to. Yes, it’s good for self-promotion, but ultimately it satisfies my soul, keeps me interested, keeps me sharp.”

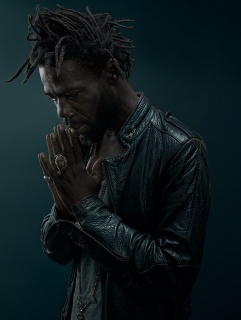

The power of Bradshaw's work is in the storytelling. A videographer as well as photographer and an aficionado of cinematic techniques, Bradshaw compares his thought process in setting up a photo shoot to a director approaching a film. It starts with a script and moves on to developing the characters and mood visually through costuming and lighting. “The image might be a guy on a motorbike,” Bradshaw says, “but the story is something deeper.”

VIVID NARRATIVE

The story of Bradshaw’s career has its share of unexpected plot twists. Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, Bradshaw moved to Perth, Australia, when he was 3 years old. As he grew, he discovered he loved biology, studying the Australian wilderness, and catching lizards and snakes, but he loved art equally and pursued oil painting through high school. “I was trying to create photorealistic paintings,” he says. And, tellingly, his photographic images today have a painterly or illustrative look to them, what he calls “hyper-reality.” “I still think painting is the greater art form; photography is the easier way to make the image.”

Despite his dual interests in science and art, Bradshaw studied law after high school. He soon switched to zoology and became a field biologist even as he was attending university. He fell into photography in 2003 at age 18 when he received a camera and used it to document his fieldwork. His zoologist salary paid for upgrades to his photographic equipment and travel opportunities, and soon he was photographing for travel magazines. In 2009, a commercial photographer in San Diego saw his work and invited Bradshaw to join his team as a Photoshop retoucher. “I wasn’t super accomplished,” Bradshaw says. “They got someone who was promising and green and learning on the job.”

The job was like an 18-month apprenticeship—“I got exposed to high-end production and how the business worked, and I learned a little bit of post-production work as well”—then he ventured out on his own. He’s since developed a clientele that includes American Express, Asics athletic wear, Diageo alcoholic beverages, National Geographic Channel, and Indian Motorcycle.

He built his reputation on what he calls an “over-the-top advertising style: larger-than-life, impossible-to-photograph scenarios.” Yet his work can’t be pigeonholed. For Wrangler Workwear, Bradshaw illustrates men in smoky, industrial workplaces, their muscular arms glistening as they perform their crafts; for Caldera Spas he shows couples and families relaxing in flowing clothes against glowing sunsets; for Acer computers he presents classic black-and-white portraits. “I do a number of different looks: surreal, bright colors, and then gritty, dark, and moody.”

He covers the spectrum in his photography for Star Trac exercise equipment. At one end is the sun-washed image of a couple hiking over a rocky desert terrain, the glaring light of the sky reflecting off the rocky surface and the hikers’ cheeks. At the other end is the image of a cage fight in a dingy, dark gym, a single hanging lamp glowing in the upper right and an off-image light casting shadows in the background. Between these extremes is a roller derby match, the young women wearing bright blue and yellow uniforms battling on a neon-trimmed track with spotlights shining through the arena’s haze. No matter the light, the details are pronounced: every crinkle of movement in the hikers’ clothes, every chiseled muscle flex as the fighters throw a punch, every scratch mark in the roller derby track.

MORE VOLUME

Given that Bradshaw apprenticed in the commercial photography business as a retoucher, you’d think such images would owe their oil-painting semblance to post-production, but Bradshaw says it starts in front of the camera: wardrobe establishes the color palette and lighting creates the exquisite detail. The images in these examples are composites—the subject is photographed in front of a green screen and separate photos of the setting and other elements are layered in. And while post-production is important, “lighting is everything,” he says. “When you’re in the real world, you’d never have eight to 10 lights on you,” as the models in the photos do. “And that’s what gives you that hyper-realistic look.” He estimates that 85 percent of the final effect of the image comes from how he sets up the shot. “Post-production enhances what’s there; it never creates what wasn’t there. You get the contrast where you want it and the shadow where you want it, and then you enhance them in post-production, dodging and burning, doing lots and lots of layers, and that’s why it looks so illustrated. But you need the lighting in the first place to get there in post.”

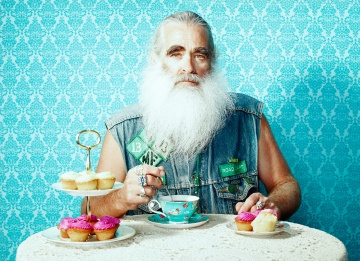

Clients usually dictate the style and concept they’re seeking based on their brand, Bradshaw says, but “every style to me is my reaction to the subject.” He pushes his own stylistic boundaries through his personal projects, some in pursuit of an interest such as his intense study of craftsmen or his Mongolian adventure, and some on a whim. After shooting a string of dark, moody images, many featuring young athletes, Bradshaw wanted to do something light and fun. He came up with a concept of senior citizens engaging in sports. Called “Golden Years,” the series features elderly men in a pick-up basketball game and aged women lifting weights and boxing. Though humorous, the bright, colorful images are intended to celebrate and empower seniors. “It’s about the unexpected heroes who aren’t typical Marvel Comic superheroes with the chiseled jaw. They are everyday heroes.”

Bradshaw approached the personal project as if it were an advertising gig. He assembled mood boards, samples of images he wanted to emulate such as old Kodachrome photos of pro athletes. He did a casting call for senior citizens with “quirky, interesting faces,” dressed them in colorful 1960s and 1970s athletic gear, and used ultra-realistic lighting to create a vintage advertisement look. “It’s all about what I’m trying to say; the story is to empower these characters,” he says. “If I know what I’m trying to say and the concept I want to put forward, I use the tools available to me: I cast a certain person, I light it a certain way, I color it a certain way. These images are built like a painting is built. Same decisions.”

But instead of a paintbrush and oils, he uses a machine, usually a Phase One IQ180 with a Hasselblad H4X body. “That machine—the camera that everyone obsesses over—has no feelings. The machine took the picture. What I enjoy is how you manipulate what is in front of the machine before you take the picture and after the machine has captured it. That’s where the art comes in.”

Eric Minton is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.

Tags: commercial photography

View Gallery

View Gallery