Photographer William Coupon’s facial obsession

Photographer Willian Coupon discusses his long career making celebrity portraits

• March 2020 issue

This profile of world-famous portrait photog-rapher William Coupon could start with the bug story. Or maybe one of the better-known anecdotes involving some of the famous people he’s photographed over the past five decades. Like the time in 1985 when he asked Donald Trump to pose for a Manhattan, inc. magazine cover portrait holding a dove, symbolizing his desire to serve as a peace negotiator between the Israelis and the Palestinians. “He agreed—grudgingly,” says Coupon. “But then the bird pooped all over his suit.”

Or the time Coupon got a last-minute assignment to photograph Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, in 1980. “He was not at all happy to be there and gave me just seven seconds. Seven! No more. But I got the shot,” remembers Coupon. “I even got him to smile.”

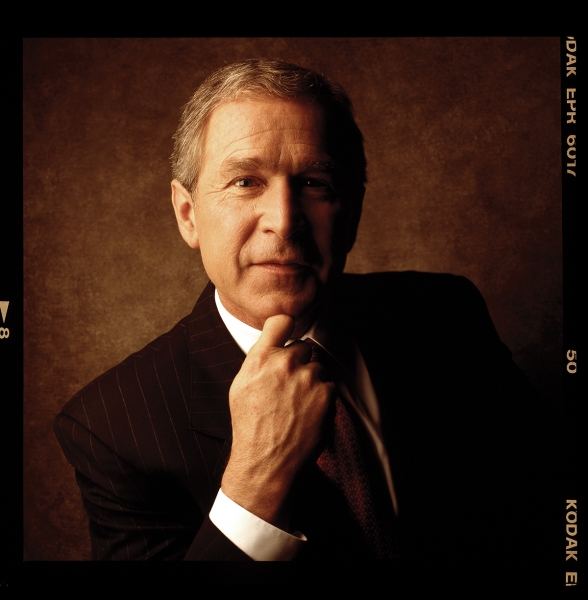

Or the time he was in Texas to photograph then-Gov. George W. Bush for a Time cover, one of 20 he has done for the weekly magazine. “Bush looked over my past work and singled out pictures of Jimmy Carter and Yasser Arafat, both of whom had posed with their hands clasped under their chins. He said, ‘No way I’m posing like that,’” says Coupon. “Ten minutes later we were finished and had a great picture of Bush, smiling gently with his hands clasped beneath his chin.”

No, this article starts with the bug story.

The first time I called longtime New York City resident William Coupon, 67, at his newly adopted home and studio in the high desert outside Santa Fe, New Mexico, he apologized: “Sorry, can’t talk now. I’ve just seen one of the freakiest things I’ve ever seen in my life. I apologize but can we talk in a bit?”

A half hour later he called back and explained: “It was a bug. It was an unreal bug! To be specific, it’s called a Jerusalem cricket but is also known as ‘old bald headed man’ or ‘child of the desert’ and was once feared by the Southwestern Indians. It’s in my front yard. It’s several inches long and has a disproportionately large head with a face that looks creepily human, like a baby’s. I was fascinated and, I admit it, a little bit scared. That face!”

All of which provided the perfect segue to remind him how he had described his career when he was just getting started: “I’ve long been interested in an obsessive pursuit of the face.”

He laughed when reminded of the quote and admitted, “Still am, I suppose. Even the faces of bugs. Kinda’ crazy, no?”

William Coupon, self-portrait, 1984

BARE BONES PORTRAITS

Coupon’s obsession with faces has helped him become one of photography’s most famous portraitists. After his late 1970s photographs of New York City-based punk counter-culture musicians and fans at Manhattan’s Mudd Club caught the attention of advertising and editorial art directors, Coupon was commissioned by magazines as diverse as Time, Rolling Stone, Forbes, and Playboy as well as scores of corporations including Nike, Rolex, Ford Motor Co., and Merrill Lynch. His signature style set him apart from competitors and kept him busy for four decades. As he has said, “I’ve shot everyone from presidents to prostitutes, rock stars to athletes, authors to actors, farmers to princes, and CEOs to surfers. It’s been too much fun to call it work. You know they say you don’t have a job when you love what you do.”

In addition to his editorial and commercial work, he’s built a massive portfolio of self-financed personal work that consists of portraits documenting subcultures and indigenous peoples from around the world. This collection, which he labels “Social Studies,” include subjects as diverse as Death Row inmates, Moroccan Berbers, aboriginal people of Australia, Native Americans, Malaysian Penan, Central African pygmies, Mexican Huichol, and many more.

“Ever since I was a kid reading National Geographic, I’ve been fascinated with indigenous peoples and exploring where and how they live, what they think. There is so much to see, to learn,” says Coupon. “I like the fact that these pictures are simple, raw, and real.” His work, both commercial and personal, has been exhibited around the world and is in much demand by collectors.

While Coupon’s subjects are incredibly varied, he’s developed a look that makes his portraits almost instantly recognizable. Some people have described “the William Coupon style.” Notes the writer Walter Isaacson in the foreword to the recently published book, “William Coupon: Portraits,” “There is a consistent and beautiful simplicity in most of Coupon’s photographs, which is all the more impressive because of his wide range of subjects. ... Each one is utterly singular, as a subject and as a personality.”

Coupon has a less elegant response to the style question: “I like bare bones, austerity, minimalism. You need to avoid all the extraneous stuff you don’t need in an image. It goes back to that idea of the pursuit of the face.”

CLASSIC BUT CONTEMPORARY

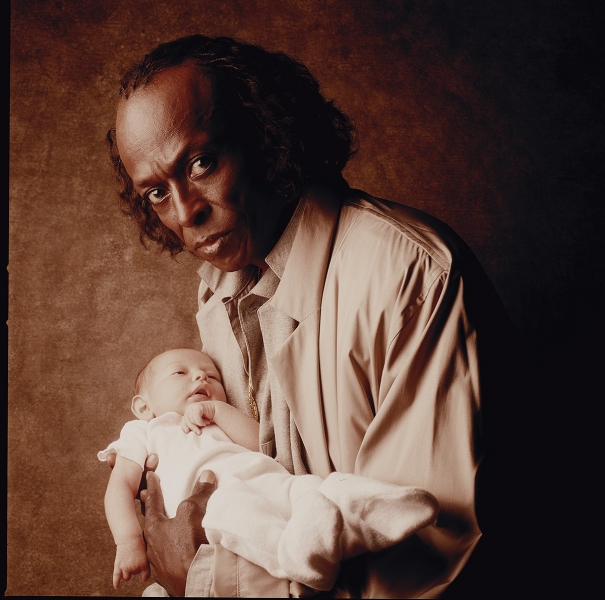

He usually poses subjects in front of his now-famous Belgian linen and heavy cotton painted backdrops that lend a painterly feel to his portraits. “The backgrounds are easy to transport, and they don’t compete with the subject,” he explains. Most compositions are medium-shot, making the face the most dominant feature.

Lighting, from a single large light box, is from the left and falls across both the subject and the backdrop, usually softening both with a chiaroscuro effect, reminiscent of Rembrandt and other old masters. Writes Isaacson, “Whenever I see a William Coupon photograph, I’m reminded of masterworks by great painters. ... The light and shadows provide both emotional and visual depth, while the blurring of outlines adds elements of mystery and ambiguity to these classic but contemporary images.”

There’s another consistency to “the William Coupon style.” Smiles are few and far between. “I only go for smiles in unusual situations,” he explains. “Usually a non-smile gives me more of a range of emotion than a smile, which is more succinct. A lot of a person’s personality can get lost in the smile. An ethereal gaze is more transcendent.” He is, however, a fan of what he dubs the Mona Lisa smile. “That’s more pensive than a full smile,” he says. “It happens when someone is looking back at you. It’s like a conversation.”

Perhaps surprisingly, given his lifetime of being commissioned to photograph the rich and famous, he confesses that he prefers shooting “real, ordinary” people, such as those in his “Social Studies” portfolios, to celebrities. “I never set out to be a celebrity photographer. I felt those pictures would be too predictable,” he says. “It just happened and was a way to pay the bills. I’ve always preferred the spontaneity and rawness of indigenous people. I wanted to find the allure in the ordinary.”

Dig a little deeper and he will explain that it can be a challenge to get celebrities to let down their guard. “Many, because they’ve been photographed so often and are familiar with the dynamic of a shoot, have predetermined positions, or what I call the ‘forced naturalism’ they fall into. They often tend to stereotype their own appearance. It can be hard to get them to relax, be natural and spontaneous, especially because your time with them is often limited.” To counteract celebrities’ tendency to control their pose, “I just shoot fast and let them get a bit off their guard,” he explains. “That usually works.”

Coupon says he’s not a big banterer but prefers to be a fly on the wall when making portraits. “I don’t like small talk but prefer to get right down to taking the picture.” He occasionally poses his subjects but notes that most celebrities don’t like much direction. “They prefer to direct themselves.” Often he will merely tell them, “chin down, lips together.” Says Coupon, “It’s almost my mantra. And it works.”

A GOOD START

As he approaches 70, Coupon explains that he is taking a break from a busy career. He admits that editorial and commercial work is not as available or lucrative as it once was, but he still looks forward to exciting assignments. He’s also arranging more personal work. Lately, he has been negotiating to photograph members of the Tohono O’odham Nation, whose lands stretch from Arizona across the border into Mexico. Several galleries sell his work, and he’s hoping to find a publisher for his personal work with indigenous peoples. A British-based publisher has also approached him to publish a collection of Coupon’s Studio 54 photographs.

“When I was in my 20s, I said that I was setting out to photograph everyone in the world,” says Coupon today as he relaxes in his New Mexico home. “I’m happy that I found a style early on, one that is simple but is always looking for the profound.”

He pauses, and as his face breaks into a broad smile, adds, “You know, I may not photograph everyone in the world but I am off to a reasonably good start.”

RELATED: A gallery of Coupon's "Social Studies" works

Robert Kiener is a writer in Vermont.

Tags: portrait photography

View Gallery

View Gallery