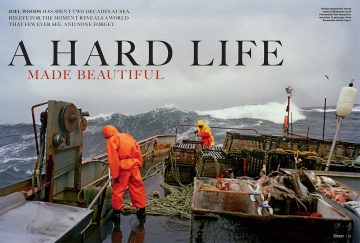

Beast on deck: Photography at sea

A Canon, fish-gutty gloves, and seawater: It’s all in a day's work for Joel Woods.

2.15.2017

Though he considers himself more fisherman than photographer, Joel Woods has made countless images documenting working life on boats. Having spent 20 years earning a living on the sea, he’s learned hard lessons in life and photography, and he’s proved his talent for creative work that captures the hardships and danger inherent in commercial fishing.

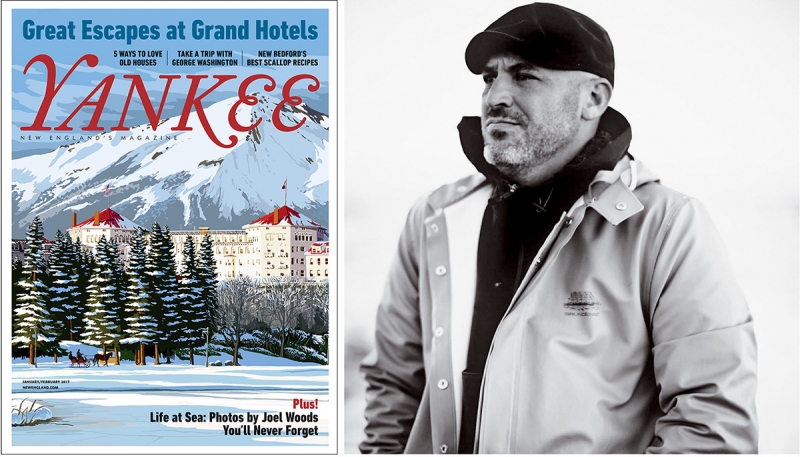

Woods’ photographs were recently featured in Yankee magazine.

COVER ©YANKEE; PORTRAIT OF JOEL WOODS ©JOEL CALDWELL

We asked Woods some questions of our own about the challenges and realities of taking photographs while working as a fisherman. His answers were bluntly honest, deep, and humorous, giving us a look into what it’s like to photograph like a pro while wearing fish-gutty gloves.

Q: You’re a working commercial fisherman who takes images that capture life on the boat and the people who fish for a living. How do you work and keep your camera at hand?

Commercial fishing is a very demanding industry to be in. You're out there to do a job, a job that doesn't pay by the hour. Any fisherman worth his salt does what he is tasked to do as quickly and efficiently as possible so that the gear can be brought aboard and back in the water as quickly as possible. He'll do this so that he and the rest of the crew can get back to shore or back to the bunk in as little time as possible.

All I can do is keep my camera within as close proximity as I can without putting it in harm’s way. Very often, especially during the winter months when I'm wearing multiple layers, I don't even have the time to take off my gloves to get a shot. If we're fishing and the gear is coming aboard, and if any one person leaves their station for an extended amount of time, then the whole process can come to a screeching halt. And I assure you, great photo opportunity or not, no one wants to be the reason everything comes to a screeching halt.

So my options are either don't get the shot, or grab my camera with bait, slime, guts, and seawater-covered gloves.

I will gladly choose the latter every time!

Q: You say you go through as many as 10 cameras a year. What's the most spectacular instance of how you lost one? And how do you line up your next? Do you stick with a certain make/model?

After taking a fairly sizable wave over the bow of the boat, an equally sizable amount of water came raining down upon me from the overhead of the wheelhouse as I was trying to get a shot of one of the boys. I pulled the camera close to my body and turned to the side in the hopes of keeping it from getting completely destroyed. Just as I did that, the boat rolled hard to starboard and the lobster tank which was next to me spilled over the top and onto my camera, finishing off the job that the wave didn't complete. But that's not even the funny part. To be honest, seawater is more often than not the culprit when it comes to the demise of my cameras. The sea giveth, and the sea taketh away.

In any event, that evening I get online and find what I'm looking for on Craigslist. The next day I pick it up. The day after that I'm back down to the boat, and while talking to somebody up on the dock, I decided to throw my bag of clothes from the dock onto the deck of the boat. This is not an uncommon act. In fact, this is usually how you get your bags aboard. This time, however, I forgot that I put my newly purchased camera in the aforementioned bag.

So that was two cameras in three days.

Workhorse: Canon T series rebel

I know, I know … this is Professional Photographer magazine. What are they doing interviewing a guy who uses secondhand cameras that can be bought new at Walmart for relative chump change?

To that I say, I really don't consider myself a photographer. I have had no real tutelage or training. I haven’t read books or taken classes. I live down the road from arguably one of the best media schools in the country, yet I'm not even sure anyone there knows who I am.

I do what I do because that’s just what I do. I don't do what I do for money. I do it because I can't not do it. It’s hard to explain, but I see my entire world in still images. I do it because nothing else on earth gives me as much satisfaction as getting a new and original shot.

Q: You mention in the Yankee article that you were drawn to fishing because it was the most hard-core thing you knew of and you wanted to prove yourself. How did that work out for you?

Firstly, offshore lobstering in Federal Management Area 3 is no joke. I think my draw to this type of fishing, and ultimately both the physical and mental strain that comes along with it, would on some abstract level be the same as someone signing up for the military and choosing the Marine Corps over the Coast Guard.

Not only are the boats larger than anything you will find inshore, the seas and storms are also larger. When you're 150 to 200 hundred miles from port, not only is going in for an approaching storm rarely an option, but when you’re that far out even the smallest of injuries could become life-threatening. Think about having to drive 20 hours to the nearest hospital. That’s a distance of roughly Maine to North Carolina by car. Now think about driving that far to avoid a storm, simply to turn around and drive back once it passes. Of course, if we think our lives will be in danger, we will do just that. But more often than not, we simply weather the storm. And I assure you, 25 to 30 foot seas in the winter are not a rarity. To put that into perspective, that’s roughly the size of your average two-story house. Now, think about working in these conditions, at night, in the dead of winter, when seawater freezes and collects on everything it comes in contact with. Having to, as soon as you wake up, bundle up so just your eyes are exposed to the cold, grabbing huge rubber mallets and cautiously walk around the ice-covered boat breaking all of the ice off the rigging because the boat is becoming dangerously top-heavy because of the ice's accumulating thickness. And the radar and running lights are so covered in ice that we can't see any approaching vessels, nor can they see us.

These are the kinds of things we have to deal with before we even start working.

More importantly, I learned very young that I didn't have to prove anything to anyone. Fishing on these boats year round for nearly five years I not only proved to myself that I could physically do any fishery, it also gave me the confidence to jump headfirst into other fisheries. Since that time, I fished out of every major commercial fishing port in the New England maritimes—Portland, Portsmouth, Gloucester, New Bedford, Point Judith, Cape May—participating in the vast majority of fisheries in each of these regions. I’ve commercially fished as far south as Chincoteague Island, Virginia, and as far north as my home here in Maine. I’ve fished as far east as Matinicus Isle, and as far west as Bristol Bay, Alaska. And I truly believe that fishing out of all of these places is a direct result of me picking the “biggest, baddest” fishery on the East Coast.

Q: Are there places and times on a boat when the other fisherman don’t want you to bring out a camera, or perhaps when there’s a mutual agreement of not-now situations?

I really can’t think of a not-now moment when the boys wouldn’t want me to grab my camera. Perhaps when there’s some sort of major problem and all hands are needed, but I would never think of grabbing my camera at that moment, so I’ve never actually heard “Not now!”

The boat that I’ve fished on for long periods of time, the boys no longer even notice when I grab my camera. And even if they did, I don’t care who you are, everybody likes a good photo of themselves.

Q: If I could ask some of the folks you’ve worked with to describe you, what would they say?

They would say that I’m bull headed and at times downright belligerent. Sometimes I’m too loud, gruff, grumpy, and outspoken, which as you can imagine aren’t always the most desired traits in a crewman. But more often than not I can make the boys laugh. But I think more importantly, they would say I’m an animal on deck. Efficient, fast, and attentive to detail.

Q: Could you talk about what goes through your head when you’re working and you see or anticipate a moment you want to be able to photograph?

I think I get more excited than anything. Try and imagine what photographing life on a boat is like. You only have a finite amount of space and subjects to capture. And as you can imagine two decades spent aboard boats, seeing something that is new and fresh, or seeing something in a new way, is more than difficult. But it is what I live for. I truly think that having such a limited amount of things, ways, and time to capture an image, has forced me to start looking at things very differently than I would have otherwise. And not just on the boat either, but everywhere.

Q: This is a little geeky, but do you have a system for switching out and stowing your media cards to try to preserve the most images if something happens to your camera?

After I capture my images, I transfer them to a laptop. After they’re on the laptop, I periodically transfer them to an external hard drive. After that, I periodically drop, spill whiskey, kick and/or crush my hard drive, rendering it inoperable. It’s a fun game I like to play! (That’s a joke. It’s not fun at all, really.)